Artists

Every Custom Prints order supports the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Subjects

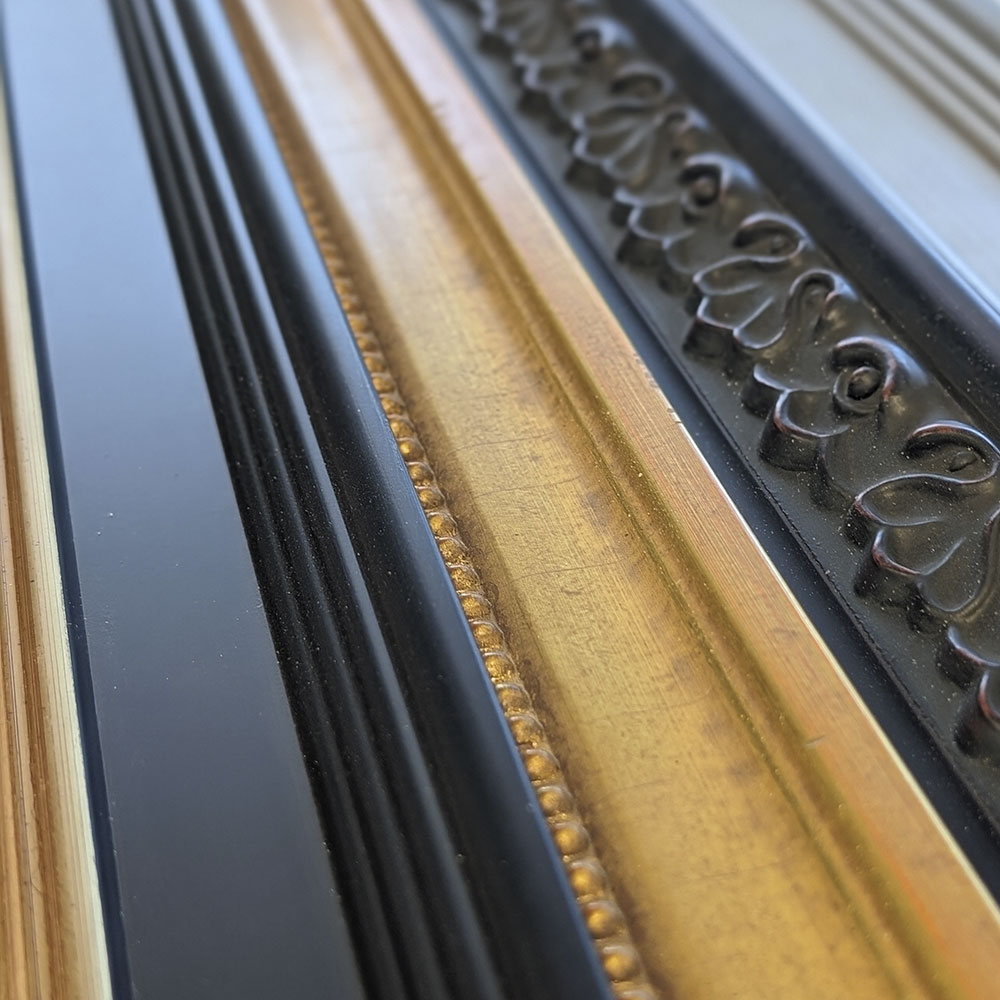

Prints and framing handmade to order in the USA.

Theme and Style

Individually made-to-order for shipping within 10 business days.